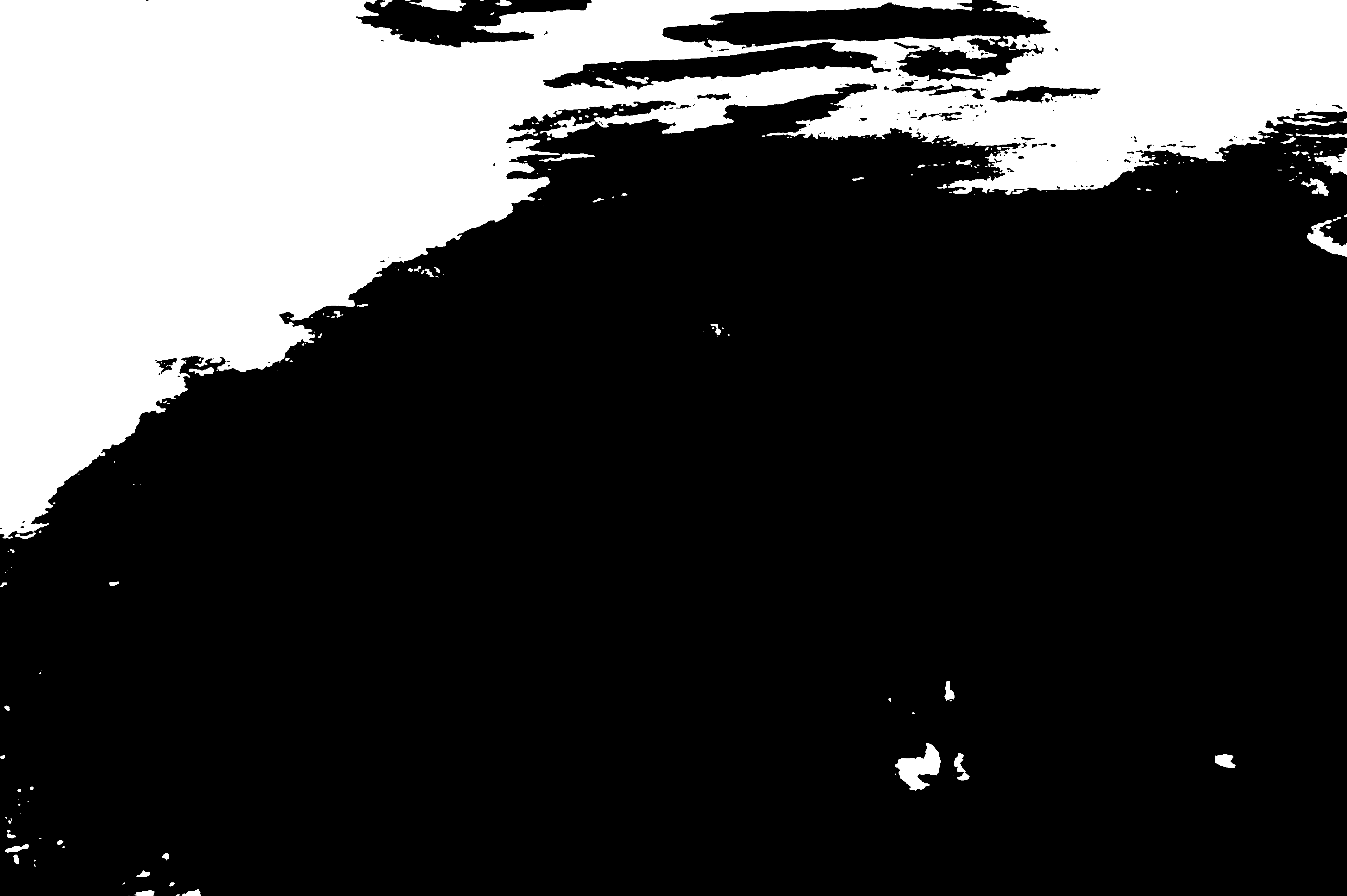

ISS038-E-47324

| NASA Photo ID | ISS038-E-47324 |

| Focal Length | 65mm |

| Date taken | 2014.02.13 |

| Time taken | 12:27:39 GMT |

1000 x 665 pixels 540 x 359 pixels 1440 x 960 pixels 720 x 480 pixels 4256 x 2832 pixels 640 x 426 pixels

Country or Geographic Name: | ARGENTINA |

Features: | SOUTHERN PATAGONIAN ICE FIELD |

| Features Found Using Machine Learning: | |

Cloud Cover Percentage: | 25 (11-25)% |

Sun Elevation Angle: | 28° |

Sun Azimuth: | 76° |

Camera: | Nikon D3S Electronic Still Camera |

Focal Length: | 65mm |

Camera Tilt: | High Oblique |

Format: | 4256E: 4256 x 2832 pixel CMOS sensor, 36.0mm x 23.9mm, total pixels: 12.87 million, Nikon FX format |

Film Exposure: | |

| Additional Information | |

| Width | Height | Annotated | Cropped | Purpose | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 pixels | 665 pixels | No | No | Earth From Space collection | Download Image |

| 540 pixels | 359 pixels | Yes | No | Earth From Space collection | Download Image |

| 1440 pixels | 960 pixels | No | No | NASA's Earth Observatory web site | Download Image |

| 720 pixels | 480 pixels | Yes | Yes | NASA's Earth Observatory web site | Download Image |

| 4256 pixels | 2832 pixels | No | No | Download Image | |

| 640 pixels | 426 pixels | No | No | Download Image |

This grand panorama of the Southern Patagonia Ice Field was photographed by a crew member aboard the International Space Station (ISS) on a rare clear day in the southern Andes Mountains. With an area of 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles), the ice field is the largest temperate ice sheet in the Southern Hemisphere. Storms that swirl into the region from the southern Pacific Ocean bring rain and snow (between 2 to 11 meters of rainfall per year), resulting in the buildup of the ice sheet.

During the ice ages, these glaciers were far larger. Geologists now know that ice tongues extended far onto the plains in the foreground, completely filling the great Patagonian lakes on repeated occasions. Similarly, ice tongues extended into the dense network of fjords on the Pacific side of the ice field. Ice tongues today appear tiny compared what an "ice age" astronaut would have seen.

A study of the surface topography of sixty-three glaciers - based on data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission - compared data from 2000 to data from studies going back to 1968. Many glacier tongues showed significant annual "retreat" of their ice fronts, a familiar signal of climate change. The study also revealed that the almost invisible (to the naked eye) losses of ice volume by glacier thinning are far more significant - 4 to 10 times greater - than those caused by collapse of the ice front (calving when ice masses fall into lakes).

Scaled over the entire ice field, nearly 13.5 cubic kilometers of ice were lost each year over the study period. This number becomes more meaningful when compared with the rate in the last five years of the study (1995-2000): an average of 38.7 cubic kilometers per year. Extrapolating results from the low-altitude glacier tongues implies that high plateau ice on the spine of the Andes Mountains is thinning as well. In the decade since this study, the often-imaged Upsala Glacier has retreated 3 kilometers, as shown recently in images taken by astronauts aboard the ISS. Glacier Pio X, named for Pope Pius X, is the only large glacier in the area that is growing in length.